Thomas Steele didn’t freak out in August after a coworker came down with a mild case of COVID-19. Steele does sales at the New Braunfels Mobile Mini, and in the office, they’d been taking precautions.

Besides, he thought, so what if he caught it? He was 54, fit and healthy — blood pressure a little high, but nothing you’d call an underlying condition. Maybe the coronavirus would make him sick for two weeks, the way it had affected people he knew. But after that, he figured, he’d be fine.

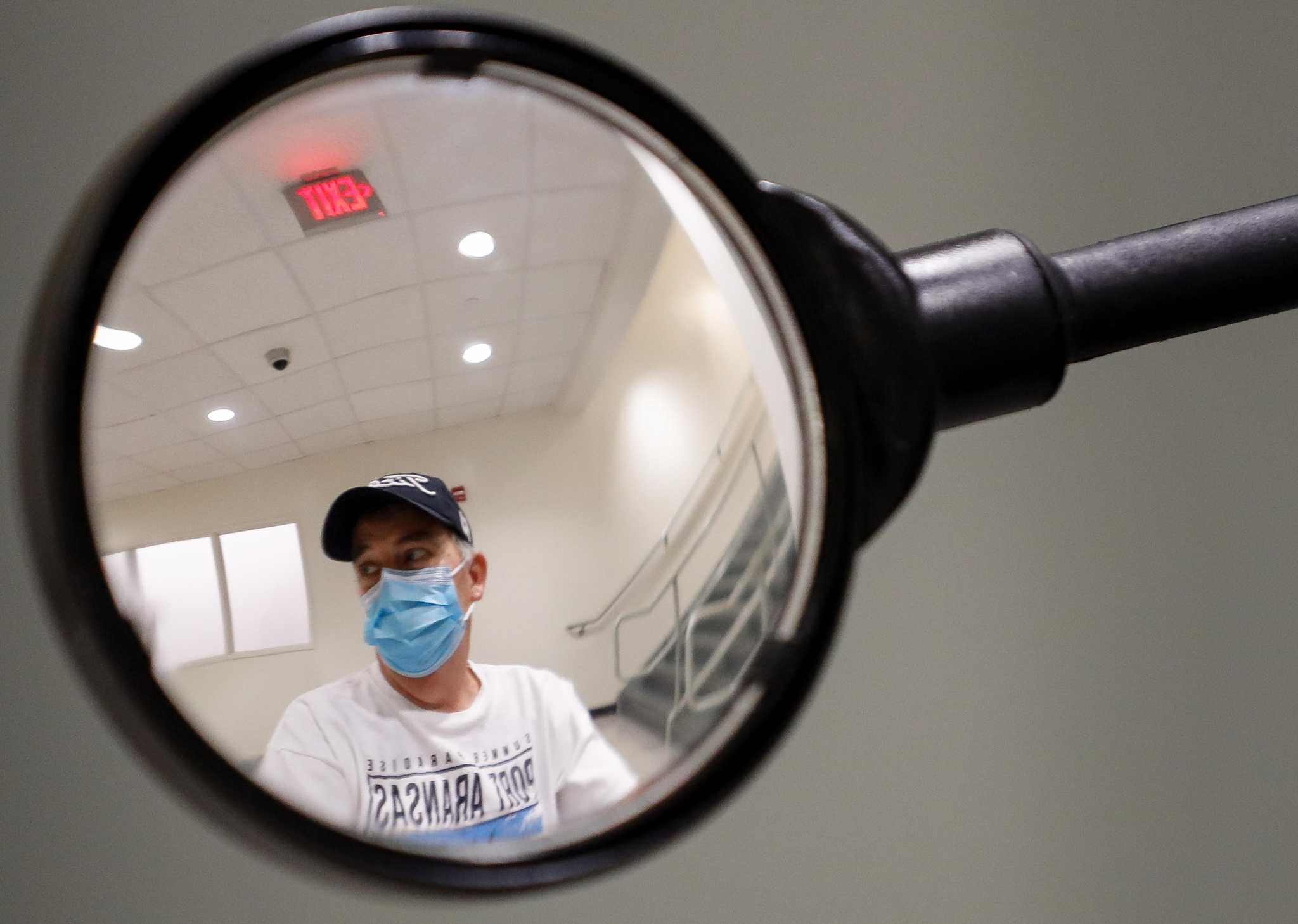

Now, four months later, he’s in Houston, recovering from a double lung transplant and more than a month on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, a particularly extreme form of life support.

“God has looked after me,” he said. “That’s why I want to spread the word. COVID is real. It’s a serious thing.”

Suffocating

When Steele had trouble breathing, he went to an urgent care center in New Braunfels. His COVID test came back negative, and he went home. A daughter studying to be a doctor made him use a pulse oximeter, a little gizmo that measures blood oxygen. His numbers kept dropping.

Two days after that negative test, he felt “like someone was sitting on my chest.” The urgent care center sent him to a full-fledged hospital in New Braunfels, one with an ICU. A new COVID test came back positive. And now he had pneumonia.

MORE FROM LISA GRAY: COVID vaccine alone won't be enough to save us, expert Ben Neuman warns

At that point, said Dr. Thomas McGillivray, Steele’s chances of survival began to drop fast. Eighty percent of people infected with COVID respond the way that Steele would have guessed he’d respond: They don’t become sick enough to need hospital treatment.

And even many of those who do need hospital treatment don’t have to be admitted to an ICU.

But for those as sick as Steele — those who can’t breathe on their own — prospects are much grimmer. During the New York City surge, McGillivray said, of the people who needed machines’ help to breathe, only 20 percent survived.

On Aug. 21, an ambulance drove Steele to Methodist Hospital in San Antonio. There he was put on ECMO, usually a last-ditch form of life support, and a relatively new treatment for COVID patients. Unlike a ventilator, ECMO acts as an external lung. One tube sucks blood from the heart and into a machine that oxygenates it; another tube returns that blood to the heart.

ECMO bought Steele time. His coronavirus infection cleared up.

But by then, it was too late for his lungs.

Conscious, he gasped for every breath. He felt as though he were suffocating.

Whatever it took

Doctors don’t usually recommend a transplant for lungs damaged by an infection: Transplants require immune-suppressing drugs, which leave people even more vulnerable to infections than they’d been before. And with COVID, only about a half dozen such transplants had been done in the U.S.

On HoustonChronicle.com: Inside a rare 'kidney swap' at Houston Methodist

But Steele’s San Antonio doctors thought a transplant was his best chance to survive. They contacted Houston Methodist (no relation to San Antonio Methodist), where McGillivray leads the heart and lung transplant team. On Oct. 7, Steele was flown to Houston.

MacGillivray braced himself. From long experience with lung patients, the surgeon knew what he’d endured for months. “There’s no worse feeling than not being able to breathe,” he said. “It’s like drowning in a swimming pool, or being smothered, or waterboarded.”

Steele, though, was more focused and far less anxious than MacGillivray expected. “Even on ECMO, despite what must have been physical torture, he’d talk,” he said. “He was positive and optimistic — looking forward, not backward.”

They discussed the risks and challenges of a lung transplant: the complicated surgery, the high number of COVID-related unknowns, the therapy that would be required. Whatever it took, Steele told MacGillivray, he was willing to do it.

Steele went “on the list” for a transplant: His lungs were irreparably damaged, but the surgeon believed a transplant would give him a good chance of survival. The question then became one of whether a suitable pair of lungs would be available in time — lungs the right size for Steele’s chest, from a donor of an appropriate blood type, lungs not likely to be rejected by Steele’s immune system.

On Oct. 21, a pair of lungs like that was rushed to Houston Methodist.

A few hours later, MacGillivray performed the first double lung transplant the hospital had ever done.

A shot of adrenaline

In November, Steele and his wife Rhonda were still in Houston. He was walking with a walker, doing physical therapy three or four times a day to build up his new lungs. There was a big scar on his chest, and he still felt a little pain where MacGillivray had cut through his muscles. The immunosuppression drugs, he knew, would change his life forever: no more sushi, no more soft-cooked eggs.

He was fine with that. He was still alive, and he felt a thousand times better now — able again to breathe. He’d seen medical images of his old lungs, with their purple dead splotches. The new ones were nice and pink. He planned to take good care of them, and to make sure other people knew what a danger COVID poses to their own nice, pink lungs.

The transplant team took their own COVID inspiration from Steele’s case. “Often, when we take care of really sick people — especially when the health system is overwhelmed — we get discouraged,” MacGillivray said. “We see too many people who die or don’t recover. But his story is a shot of adrenaline in our arms. He’s a reminder that even the very sickest people can get better.”

lisa.gray@chron.com, twitter.com/LisaGray_HouTX

"later" - Google News

November 27, 2020 at 10:30PM

https://ift.tt/3mdp3OV

COVID didn’t scare him. Four months later, he’s recovering from a double lung transplant. - Houston Chronicle

"later" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KR2wq4

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "COVID didn’t scare him. Four months later, he’s recovering from a double lung transplant. - Houston Chronicle"

Post a Comment