This story is part of a package on the one-year anniversary of the COVID-19 lockdown.

It’s been the worst of times, it’s been…the worst of times. A year ago on this day I brought home the laptop I’m typing on right now from my office in midtown Manhattan and haven’t looked back. (I did go back, just once, to TCG headquarters, which, other than having been dutifully cleaned, seemed preserved like Pompeii in their March 2020 state.) I had spent the previous weeks getting on and off buses and subways, going to the theatre and church and assorted public places—including Madison Square Garden for a concert—all while wondering about this sneaky new virus. Was it in the air? Would we be going into lockdown soon? Would that be too little, too late—or an overreaction? And what would that mean for life as we knew it?

Twelve months and half a million dead Americans later, among the few things that is clear is that COVID-19 seems to be evolutionarily optimized for an age of political polarization and epistemic closure: just fatal enough to become the leading cause of death and immiseration in the U.S., not fatal enough, apparently, to impress on many individualistic Americans the urgency of collective suppression. And so it rages on, even as vaccination numbers climb toward a semblance of hope. The material dangers, as well as the psychological trauma, of a year of distance and death mean that among the last human activities likely to return to anything like a pre-pandemic “normal” is live performance, even as we ache for it.

But even with little or no live theatre to speak of, we have nevertheless had no shortage of people and things to write about, whether it’s been the theatre field’s struggles with adversity or its adaptations to it, its fears for the future or its fierce, queasy hopes about the possibility of true transformation. In addition to our usual coverage, after lockdown we immediately commissioned a still-ongoing series, Dispatches From Quarantine, to take the pulse of the field and its workers. Further inspired by the opportunity this pause has given for reflection and reassessment, and spurred by the anti-racist We See You White American Theater movement and others like it, we also launched What Is to Be Done, a column for arts leaders and workers alike to give us their visions for change—to take big swings at antiquated models and advocate for new ones.

One thing that has stuck with me through this year of pain, isolation, and uncertainty is a line from Idris Goodwin’s Dispatch, which he wrote for us way back on March 23, 2020. “This ain’t the intermission. It’s the show,” Goodwin wrote, as if preemptively throwing down the gauntlet for any who might be tempted to merely hibernate or sleepwalk through lockdown. “This is the moment where everything changes. We are in the inciting incident.”

So what happened—what changed—in this past 12 months, and how will this lost, frantic year be remembered? I asked dozens of theatre workers from all over the U.S. to answer those questions. Their responses are a panorama of grief, gratitude, frustration, affirmation, resolutions and questions. I’ve often said this magazine is only as good as the people it covers, and this past year—a year in which I had many fewer chances to see the art U.S. theatremakers usually put on stages in front of me, but nearly as many chances as ever to talk and connect with them about their lives and work—brought that home to me all the more.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him), editor in chief of American Theatre

Stretch Before the Mad Dash

As with many of my peers and colleagues, my work in casting seemed to grind to a halt virtually overnight. This happened, however, to coincide with a timeline I had been attempting to create that would return me back to living on the West Coast again, and in a slight haze of survivor’s guilt from having made it thus far without contracting the COVID-19 virus, I feel it only fair to acknowledge that the first of what would end up being many silver linings revealed itself: I was suddenly untethered to my locale. In less than a month, I began a 14-day quarantine back at my parents’ house in Langley, a small seaside village on the southern end of Whidbey Island in Washington state.

Around the same time that demonstrators in Seattle had formed the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP) and a subsequent media frenzy reached international recognition, I moved back to the city and attended my first protest in response to the senseless murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and too many others by corrupt police forces gone unchecked for far too long. The presidential election, the declining condition of my only living grandparent, and the ongoing assault on the dignity and right to autonomy against us in the trans community raised my awareness to a dialed-up level I had never imagined possible in such a short period of time. It never felt so obvious in my whole life just how much of this planet I share with other people as it has in the past year.

Suddenly, contracts began arriving. The most inconceivably wonderful housing situation appeared. I am back in the city I so desperately craved to return to, close to my support network and my wonderful family, continuing my work in the industry I love. The road to prioritizing my mental health and the better work that has begun to reveal itself as a result is something I am allowing myself to be proud of; the fact that it began at a time of such trauma and chaos for the world is a matter I’ll likely be processing for a long time.

As for the theatre community at large, I’m concerned we’ll return from this haze and go right back to overworking our bodies and minds, and our art will suffer for it as a result. Will we remember to stretch before we begin the mad dash? How will we tend to the inevitable wounds if we opt into the marathon with little preparation? Or, is there still time to re-shift, refocus, and come back with the livelihoods and well-being of our employees at the forefront of our operations? This requires a reckoning, one that dismantles an ivory tower we have collectively been propping up for a few white men with a lot of power for far too long. We see you, as you definitely now know. We’re shaking. Perhaps hard enough to cause cracks. Perhaps hard enough to swallow the entire thing whole.

Ada Karamanyan (she/her), casting director

Yes and No

I started the year thinking I had to say yes to any panel, any event or opportunity to teach. I wanted to show love through these engagements. But such things make me deeply anxious. I couldn’t sustain it. I had to remind myself that creating story is an act of love, a perfectly viable way to stay in it.

So I started saying no to anything that sent me on an anxiety loop. I wrote when I could and gave myself a break when I couldn’t. I ate what I wanted in spurts: fried catfish and mac and cheese from a favorite soul food spot, homemade Korean BBQ, lots of lentils, and sticky garlic tofu. There was also a serious Chipotle phase. I binged baking shows, sitcoms, true crime podcasts, and reality TV.

I started and quickly abandoned regular workout routines. But I found that I could walk for two miles along the walkway in the center of my apartment while listening to podcasts. That stuck. I strengthened relationships, going on Sunday hikes with one friend, epic Friday evening happy hours with another, and the occasional bookish check-in with an East Coast buddy.

I’ve given myself time to mourn, to grieve, and to respect the inevitability of death. Cycles don’t quit. I finished a weird play. I wrote a draft of a screenplay. I wrote a short horror audio play. I’ve read many books at the same time. It is slow but lovely. I protested. I made donations. I knew it wasn’t enough, so I started planning to create the kind of respite I want to see, a place where folks, especially Black women, can make things (or not) in peace.

I will look back on this as a time when I was reminded that I get just one self. One Aleshea. And she doesn’t grow tentacles or excess stores of stamina just because people want her to do things. She gets to rest. She’s more effective that way, more useful.

Aleshea Harris (she/her), playwright and screenwriter

The Truth Is Out

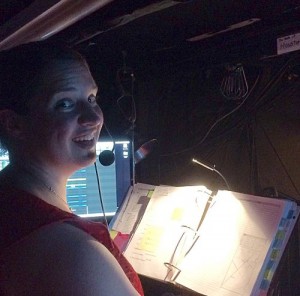

2020 had already been designated as the Year of the Stage Manager, before the industry was turned upside down. I liked behaving as though the idea for the campaign simply fell from the sky, so that a greater number of people would buy into it. The truth is that a sound designer, Lindsay Jones, and I invented it. We both felt that the stage management community would benefit from an entire year focused on celebrating stage managers and educating people about what they do.

As we all know, 2020 did not go as planned—for the first time in years I was forced to sit still in one place. While my show gathered dust inside the Lyceum, the Year of the Stage Manager Facebook Group grew to over 8,000 members, and I was hosting two free Zoom events per week, focused on giving stage managers a platform and visibility. Remarkably, the pandemic provided the opportunity for stage managers to connect from all over the country, some from opposite sides of the globe. We were able to shake out all the affinity and conflict our individual experiences afforded us, leading us to not only question what we thought to be universal truths about our field but also strengthen our community through greater understanding.

Year of the Stage Manager was designed to expire—the idea being that stage managers would have to get really loud before the clock ran out. We extended the campaign into June of 2021, the times being too tumultuous and the gift we found in each other too great to leave buried inside 2020. When the industry tipped over, out with it came the ugly truths about the way laborers regard themselves in the arts and how deeply rooted white supremacy culture is in our practice. From taking the time to listen to my colleagues, I have learned so much about what I would do differently as a stage manager and what I will change as I move forward.

We must no longer apologize for choosing a professional life in the arts, and we must no longer be our own worst enemy by treating ourselves as anything other than a laborer deserving of humanity, safety, and a living wage. Every day I am pushing back at what has made me comfortable, what has made me feel successful, and remodeling the fractured pieces of what was once familiar.

So how did I spend my time? I filled it with stage managers. I filled it by spending time with all the dismantled parts of a profession that was second nature to me. I filled it with learning. I filled it with listening. I filled it with friends. I filled it with family. I filled it with being a mom. With more space. With more time. With more honesty.

How will the industry look back on 2020? I hope we look back on it as a gift. We would be foolish not to. The business is beginning to right itself, and people are filled with fear that nothing will have changed when it returns. But it has already changed; the truth has been strewn about, it is everywhere. And the echo of what was unearthed during our hibernation will ring throughout the theatres, as they turn off the ghost lights and lurch back to life. A new life, reborn of a year like no other: one dedicated to stage managers and, I hope, deeply fruitful for us all.

Amanda Spooner (she/her), stage manager

Cambio

On Feb. 14, 2020, I found myself sitting outside a small conference room at Yale School of Drama anticipating my interview for the Theater Management Program. Holding on tightly to a silver charm of the drama masks my sister sent me for good luck onstage when I was 12 years old, I felt like my entire life led me to this moment. I was confidently pursuing my dream of applying to Yale, something I thought about often in the years leading up to this. In late March, I received a life-changing call from the program director welcoming me to the incoming cohort of seven. I was thrilled.

Little did I know that my first year of a hands-on theatre conservatory program would be spent on Zoom and that my three-year MFA program would be expanded to four years. But like many of us have been asked to do this past year, I’ve leaned into the uncertainty and have tried to ease my pandemic anxiety by embracing change. I knew my entire life would be different once I went back to school, and this is exactly what has happened. I left a job of five years that I really loved. My long-term romantic relationship came to an end. I haven’t sat in a theatre, a weekly outing in the before times, for over a year now. My chihuahua Bella lost her second eye due to glaucoma.

And in the next few months, I will have to say goodbye to New York City, the beautiful, resilient, gritty place that made me and that I’ve called home for eight years. I know that I’m simultaneously grieving all of these things in ways that I’ve yet to understand, but I also know that we’re all grieving. When my mom hears uncertainty in my voice, she says, “Para adelante, mija.” This is exactly what we are all trying to do. For me, embracing change is part of embracing the future, and I have to remain hopeful and excited about that.

Annabel Guevara (she/her), MFA Candidate 2024, Theater Management, Yale School of Drama

Missing and Not Missing

I’ve spent this time reconnecting with my family and missing the alchemy among my scene partners onstage and the collective laughter of an audience. I’ve been missing post-show drinks and finding new ways to think about the trials and mysteries of existence sitting in a dark theatre. I’ve missed design. I’ve missed out-of-town workshops in rustic places where I only had to worry about investigating a new play truthfully enough to serve the playwright. I miss the Season that Might Have Been: for me, for my friends.

I haven’t missed what theatre has cost me over the years: being paid less than minimum wage for over 40 hours of work, with little to no health insurance; having to perform sick or with injuries because there was no understudy and I didn’t want to let everyone down; having to turn down higher-paying work out of obligation when little obligation was shown me. I don’t miss microaggressions and having to tread lightly around white egos (as virtuosic as I have become in that!).

This past year, I’ve watched the American theatre begin to reckon with itself. I’m looking to see if that reckoning bears fruit when we reopen and what we laborers may reap. I’m looking forward to returning to an American theatre that puts its money and programming where its mission statement is. A theatre where previously underrepresented people are empowered, well-paid, and free to tell their stories boldly, quietly, sexily, heartbreakingly, gloriously. I’m looking forward to a theatre that gives artists as much as it gets from us, a theatre that shows us it loves us as much as we love it. Because I do love and miss it so.

April Matthis (she/her), actor

Resting, Reimagining, Restructuring

This universal pause forced all artists to reckon with our identities outside of our professions, a rare and terrifying prospect under the system of capitalism which equates our productivity to our worth, our job to our personality, then has the audacity to pay less than a living wage. Who am I if I’m not #booked?

After a deep depression and with the help of therapy, I rediscovered parts of myself I had let gather dust as I ran myself ragged with work pre-pandemic. I spent the year saying no to projects I don’t care about, and that reclamation gave me permission to focus on decolonizing my art practices and producing work by and for BIPOC artists only. I restructured my digital rehearsal rooms many times in an attempt to find a non-hierarchical structure that elevates the work without exploiting the actors who embody it. In every production I’ve been apart of under white leadership, actors of color are made to bear the entirety of the intellectual and emotional labor around discussing or navigating the racial dynamics in the play under the guise of “collaboration.” As a director, you set your BIPOC actors up for active harm when entering a rehearsal process without a clear perspective of how race functions in the script, without considering the racial dynamics of the people you cast to perform it, and without a trauma-informed plan to address it.

As a multidisciplinary artist, I am grateful to spend a year off of performing so I could pour into my community as an organizer, writer, and director to advocate for actors from positions of power. But considering all that has happened this past year, above all else, I’m truly and deeply grateful to be alive.

Arti Ishak (she/her), actor and director

Leap From Day to Day

I have spent the past 12 months asking, along with the folks at Playwrights Horizons, what a theatre can possibly do from a distance. The answer hasn’t been too far off, I think, from what many of us might have been doing during these long, lonely months: looking inward, rooting around, getting a little clearer on how we want to be in the world artistically, politically, spiritually.

When I remember this year, I might think of those strange early days in Manhattan on my own, watching the mid-morning sun shimmer across the carpet and, later in the evening, stumbling through a new section of Chopin’s Nocturne in E-flat major. By late spring, when Playwrights Horizons was beginning to pivot away from a season and toward a magazine (the better to keep in touch with artists and audiences), I was baking bread with 50 pounds of flour I’d ordered wholesale. In the period between George Floyd’s death and Juneteenth, the theatre was abuzz with questions of power and privilege and protest.

Then, in July, many of us were furloughed. I tended three jolly tomato plants and played Magic the Gathering for the first time, my deck full of whites, blacks, and greens. August brought me to the easternmost edge of Queens and back to Playwrights Horizons. Work on the theatre’s new magazine deepened, rivaled only by our work towards more equitable and inclusive policies and practices. We pored over the #WeSeeYou demands, letting them echo through Google Doc after Google Doc. The fall and winter were lit by a string of festive fairy lights in my front window. With macramé and Pokémon to look forward to at night, I made strides on my dissertation each morning. Now the magazine is done, our commitments to anti-racism are holding us to account, and I still haven’t seen my family.

Plodding on with my projects and seeking refuge in reliable comforts, I don’t feel like I’ve stopped long enough to let the pandemic really settle on my soul. I don’t know if the theatre has, either. My sense is that we’ve tried to keep doing, keep living, as best we can, without pause. When we look back, maybe we’ll see all the loss like ice falling from a glacier in great sheets, sending up spray and leaving little still standing. But right now, a year in, with the end not yet in full view, I’m just trying to leap from day to day without totally losing my balance. I’m placing my trust here, in the fits and starts of growth that eventually, I hope, might gather into something more.

Ashley Chang (she/her), dramaturg, Playwrights Horizons

Hitting a Wall, Finding a Silver Lining

The initial weeks of the shutdown were very busy, as it required me to report on the unprecedented amount of cancellations and, inevitably, the flood of closing announcements. While I tried at first to celebrate theatremakers who were finding ways to adapt—filming productions, teaching classes, or writing pieces set in the pandemic—I hit a wall and had to step away. Looking back, I think I was ultimately heartbroken at the fact that this industry I love so much largely disappeared overnight, and countless arts workers were suddenly out of work. Add to that the sadness of mourning theatre names like Adam Schlesinger, Terrence McNally, and Nick Cordero, all of whom died from COVID-19.

With everyone sheltering in place and filling their free time with massive amounts of at-home entertainment, I was reassigned to cover television. Journalistically, this time away from theatre coverage has been an education, as well as a means for me to heal from my shutdown despair. It has also, surprisingly, yielded some of my strongest theatre journalism to date, including an appendix of anti-Black behavior in the white American theatre, an exploration of what stage actors contribute to the characters they originate, and a plea to Hollywood to actively invest in the theatre.

I don’t know if I would have been able to pull off these pieces if it weren’t for the shutdown, as the momentary distance from this industry has helped me to see it more clearly—for what it is and for what it can become. (Not having to deal with Los Angeles traffic probably helps too.) At least as a silver lining, I’m thankful that this moment has amplified so many important conversations about equity and inclusion, and given me a chance to report on them in thoughtful ways. I look forward to continuing these conversations in my work when theatres reopen again.

Ashley Lee (she/her), staff reporter, Los Angeles Times

Awe and Frustration

It’s been a year of the highest highs and lowest lows for me and my relationship to the theatre. As I type this, I sit in awe of the persistence and dedication of theatre artists. How heroically they forged ahead and tackled a new medium. The resiliency of theatre people, my God!

And also, also, I feel deep frustration at the sudden “awakening” of the powers that be. These “statements” they put out—no mames, how were they this unaware of how unjust their system was? I love the pinche theatre now more than ever. And pray as we begin to create a more equitable and inclusive art form. We must in order to survive.

Bernardo Cubria (he/him), actor and playwright

Just Talk About the Thing

What a wild question to actually sit down and think about. I’ll be real, I spent most of the last 12 months in a deeply paranoid, agoraphobic, hypochondria-ridden haze. I moved home with my parents. I shaved my head. I also spent time frustratedly working from home, taking an ASL class online, learning how to bake cakes, and binge-watching every Disney animated movie in chronological order. I did not read a play for six months.

I also spent lots of time just thinking, often about theatre: missing theatre, hating theatre, interrogating theatre, yearning for theatre, bashing theatre, cherishing theatre, and a lot of apathy for theatre. Theatre is a lifeblood to me, so to both feel so far away from it as I’ve gone longer without doing or seeing a show than I ever have, while also feeling so close to it as I reckoned with how I make my way through this industry, was very strange and unsettling. I spent a lot of time trying to find my place and my opinion in the world today in a way that is based on my own values and morals. I spent a lot of time having really uncomfortable (but necessary) conversations with friends and colleagues.

I hope we look back and realize that Zoom readings are a terrible fucking idea. I’ve done them and I hate them. I hope we’re prepared to be in this for the long haul. I hope we are intentional about how we move forward. I hope we can just talk about the thing finally. Whatever that thing may be—racism, misogyny, equity, salaries, access, whatever—let’s just talk about it. That’s the first step towards fixing it.

I’m looking ahead with an understanding that capitalism is the real enemy while trying to come to terms with the unfortunate reality that I will both fight and embrace that enemy at different times in the future.

Brandon Ivie, associate artistic director, Village Theatre

Toward a New Normal

Joni Mitchell’s insight that “you don’t know what you got ’til it’s gone” couldn’t have been more prescient as the pandemic brought in-person performance to a halt. And with theatre productions postponed or cancelled, artists both on- and offstage could only wonder just how devastating the health crisis would be to their livelihoods.

Still, the creative impulse could not be extinguished, as theatrical activity moved online and Zoom became the new stage. If it wasn’t theatre in any traditional sense, the virtual productions that initially reminded viewers of the old Hollywood Squares game show proved diverting in their own right. And some forward-thinking artists imagined a scenario in which they might still be around in some fashion after things got back to something resembling normal.

But is the old “normal” really what we need? As bad as the pandemic has been, it has called attention to the precarious economics of American theatre—particularly the lack of support at the federal level as compared to that provided in other industrialized nations.

In the best of times, many theatre companies from coast to coast struggle to make it from season to season. In a new “normal,” that needs to change.

Calvin Wilson (he/him), theatre critic, St. Louis Post Dispatch

Reinvention and Attention

March 2020 seems a thousand years ago. At the time, La Jolla Playhouse had just opened our new musical Fly, while the Performance Outreach Program (POP) Tour, our annual play for young audiences, was heading into San Diego schools. In New York, two Playhouse-born musicals were running: Diana had just started previews, and Come From Away was about to celebrate its third anniversary on Broadway. Then, almost overnight, everything shut down.

While the past 12 months have been devastating for the arts, I’ve been heartened by the amazing and inventive ways artists and theatres have found to connect with audiences, from Zoom readings to streamed productions to online master classes. The Playhouse launched a digital arm of our site-based, interactive Without Walls (WOW) program, where we were able to continue paying artists and staff to create 14 original Digital WOW pieces, made specifically for this moment. Serendipitously, these productions ended up breaking many barriers to access, growing our reach and introducing thousands of new national and international audience members to the Playhouse.

The past year also saw a profound, industry-wide reckoning around systemic racism. Our entire staff and board came together to urgently reexamine the art on our stages and our practices in every aspect of our organization. Like many institutions across the country, we drafted an Anti-Racism Action Plan with concrete steps for the short and long term to make our theatres more inviting and inclusive to BIPOC artists and audiences. While there is still much work to be done, I have been energized by the conversations and commitments of the entire theatre community to make deep, lasting changes, both on stage and off.

Looking forward, I join my colleagues in keen anticipation of a return to live performances. Yet I also fervently hope we can continue to make time for institutional reflection, and that we keep expanding and reimagining the ways we create art, as well as the people with and for whom we create it.

Christopher Ashley (he/him), artistic director, La Jolla Playhouse

A Slow But Sure Return

I remember being on a conference call a year ago with my cast and production team of Cost of Living by Martyna Majok at Round House Theatre on the day it was decided to halt rehearsals for the show. We all had our calendars out trying to decide what dates in late summer/early fall of 2020 we would be available to resume rehearsals, because surely this quarantine would not last long…

The next thing we knew, all hell had broken loose. There was going to be no livelihood (“Wait a minute, everything is cancelled?”), no answers (mask/no mask? how long before we can bring groceries into the house?), no peace (Ahmaud, George, Breonna), and no life. It was a scary, stressful time with no end in sight.

Gradually, though, we found ways to create art. We all became proficient in Zoom, ring lights, and green screens. Cancelled productions became online readings and radio plays. And in the midst of the pandemic, there was some hope for a future. It was a tenuous hope, but we clung to it.

Fast forward a year and I am back at Round House, directing Colman Domingo’s A Boy and His Soul on site in full protective gear, to be filmed and streamed to audiences in their homes. We definitely have some distance to go before we return to any type of normal, but I am grateful to have made it this far and so ready to encounter what’s next.

Craig Wallace (he/him), director and resident artist, Round House Theatre

Someone Tell the Story

The power of art and imagination is undeniable and unstoppable. We’ve seen our community rise up this past year to create art in inventive and thrilling ways. We’ve seen an outpouring of support for those in our community suffering the most. And we’ve seen audiences engage virtually, with gusto, hungry for theatre content of any kind.

Being in a unique position as co-founder and CEO of the Broadway Podcast Network when the pandemic hit, gave me and our incredible team the opportunity to dive in and give these great storytellers and theatremakers a platform to create art, tell stories, and keep theatre alive during this difficult time.

As the world ramps back up, art will continue to lead the way, challenging our assumptions and expanding our understanding, and pushing us to see things in new and unexpected ways. Our community of amazing storymakers will continue to bring us all together like nothing else can: with joy, with reflection, and with hope. BPN will be right there to amplify these voices, to create cutting-edge virtual storytelling, and to support shows and theatre organizations as they welcome back audiences on Broadway and way beyond.

Dori Berinstein (she/her), producer and CEO, Broadway Podcast Network

The Glow of the Virtual Campfire

Over the past year the Pacific Conservatory Theatre – PCPA has developed a mantra of sorts that we share with our audiences after each piece of virtual programming, a reminder to our community and ourselves: “While our stages may be dark, our lights are still on.” For the time, stage lights have been replaced by the glow of home offices, home studios, ring lights, and computer screens. During the last 12 months, these lights have remained on at full strength to illuminate the work we’re doing in “our own backyard” and in our virtual programming with PCPA Plays On!

One of the primary offerings of PCPA Plays On! has been the pivoting of our play reading series, InterPlay, to a virtual format. In the fall of 2020, we expanded our previous in-person three-play reading series to offer readings of six “fresh picked plays” (so called as a nod to the amazing agricultural community that we serve here on the Central Coast) virtually over six weeks, with a goal of featuring diverse voices and immediate stories. Among many great and timely plays, this fall’s InterPlay offerings included a serendipitous reading of Mat Smart’s The Agitators on the evening and weekend of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s passing. That series garnered an outpouring of grateful responses from our audience, who were hungry for theatre and connection, many of whom joined us from across the country and even across the world. So we’ve brought the series back this spring and are currently in the midst of reading four more fantastic plays.

PCPA has been continuing to serve and connect with our community in other ways as well. As a professional conservatory theatre, we’ve had to take a hiatus year in our own classrooms, but our faculty has stayed busy offering virtual classes for the community as well as in-school workshops for junior highs and high schools in our area. Continuing the company’s childhood literacy campaign, PCPA Reads, we created and shared an entire video library of children’s books read and performed for schools, libraries, and local children’s organizations. For grown-up readers we established a play reading and discussion club of classic texts. Over the holidays the theatre created and shared a popular Home for the Holidays Cabaret.

And in our own backyard, we’ve been using this pause in production to fully engage in the imperative Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion work, including multiple full staff trainings, as we deeply reexamine many of our institution’s operating practices, reassess our conservatory curricula and structures, establish an EDI Committee to facilitate this on-going work, and engage in the essential personal work that is needed to support these positive shifts.

What I’ve learned in the producing of the InterPlay series and our other virtual offerings is that, while this work is quite challenging in new and unexpected ways, it has actually been deeply reassuring to myself as a theatre artist and as a human. People are still hungry for theatre. For connection. Maybe even more now than ever. To be told a story that can simultaneously lift them out of their own experience and connect them to a universal human experience is a need as old as time: the gathering around a fire, the source of light in a long dark winter, and to be told a story. In this long winter of the arts, the glow of that fire may have been replaced by the glow of a screen, but we still gather around the light to hear a story.

Emily Trask (she/her), actor, literary associate, and resident artist at PCPA

Keep the Kindness Going

Last July, during the height of the pandemic, I began my new position at Yale School of Drama/Yale Repertory Theatre. As theatre leaders around the country were immersed in furloughs, salary cuts, insurance claims, PPP applications, and making and remaking production schedules, I was able to focus on the next generation of theatremakers. I consider myself the luckiest person in the theatre. Working remotely, I have never seen my office and I haven’t met most of my colleagues in person, but that hasn’t stopped me from calling them my friends.

The entire school is focused on anti-racism, developing curricula in every discipline. We consider ourselves co-learners in this challenging and life-affirming work. While students, staff, and faculty are eager to get back to production, we realize we must come back with more equitable practices that center Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) artists.

My life has changed completely. Gone are the quick dinners in the theatre district just before a show or tech rehearsal. Instead my husband and I dine at home, watch Netflix, and read with our adult autistic son via FaceTime. I have not seen my daughter in over a year, as she works in theatre in London. I miss her so much. Still, our challenges are nothing compared to those of so many artists, artisans, and theatre professionals who have been unemployed, or families supervising school for their children while working, or special needs families with no support system, or those who looking after elders. I am very fortunate indeed.

Years from now, I hope that we have not forgotten those who lost their lives to COVID-19, and I hope the care and kindness that we extended to one another during this time will have become the norm in the theatre.

Florie Seery (she/her), associate dean/managing director, Yale School of Drama/Yale Repertory Theatre

Move Toward the Light

On March 12, 2020, I flew from Los Angeles to Ft. Lauderdale to watch my 14-year-old niece, Shelby, act in her first play. The year prior we’d spent months, at her request, preparing for her audition for Dillard Performance Arts High School. Days before her audition, she desperately asked, “Auntie, do you think I have a chance?” As any loving aunt would, I replied, “Are you kidding? They’d be crazy not to accept you!”

Truth is, I was worried. Not about whether she’d get in or not—I had no doubt she would. I was actually worried about what would follow when she did get in. What would happen if she fell in love with theatre, just as I did at that age? What if it became her passion, her profession, her vocation, her life? I wanted to protect her from a life of rejection, of disappointment, of cutthroat competition, of financial instability, of heartbreak. I know, right? Project much?

Needless to say, Shelby’s school show did not go on. Like theatres all over the country, the school shut down that week and stayed closed for the remainder of 2020. What this last year without live theatre has taught me is that all the things I love and miss about theatre far outweigh the fears and anxieties I projected on to my niece. I was so focused on the ways the industry can hurt and disappoint. But 2020 reminded me of the ways the art of theatre loves. Theatre heals. Theatre connects. Theatre teaches. Theatre activates change and even revolution.

And probably most evident in this past year, no matter what, theatre survives. I am in awe of the ways my community has demonstrated this truth, and am immensely grateful for the opportunities I have had to create, connect, heal, and teach through my own work. In July 2020, I was one of four female-identifying playwrights, representing the African Diaspora, commissioned to write plays in response to the prompt “Conversations with the Ancestors.” A production of Project Y Theatre, All Hands on Deck streamed throughout the summer.

From April through December, I hosted “Saturday Matinees” with the Fountain Theatre, a virtual salon that featured theatre artists from all over the country, including Kit Yan, Antonio Lyons, Lisa Strum, Dennis A. Allen, Vanessa Garcia, and more. The weekly series celebrated BIPOC artists, while providing audiences time and space to connect with each another during a time when many of us endured incredible isolation. In November, I led a four-week workshop hosted by Global Voices Theatre in London. Participants joined from all over the world—Hong Kong, Philippines, India, the U.S.—to develop new plays aimed at correcting revisionist history.

In January of this year, my play Tigress of San Domingue streamed as part of Atlantic Theatre Company’s African Caribbean Mixfest, and last month I was among six playwrights featured in Long Distance Affair. Produced by Juggerknot Theatre and Popup Theatrics, LDA brought together playwrights and actors from six cities around the world—Los Angeles, Portland, Beirut, Lagos, Mexico City, and Mumbai—to create immersive theatre. With over 60 live performances, LDA is the closest thing to in-person theatre I experienced all year. Audience members interacted with one another in intimate Zoom rooms, and with the characters whose lives they interrupted, often at odd times depending on the city (2 a.m. in Lagos).

I had the pleasure of collaborating with L.A.-based actor Wendy Elizabeth Abraham, who bravely invited us into her home in Sherman Oaks, and into her emotional journey through grief and motherhood. I attended about six of the 60-plus performances, and no two were ever the same.

Finally, I launched Fountain Voices, a new arts education initiative I developed in my role as community engagement coordinator for the Fountain. The program promotes empathy and community building, teaching students how to write original plays based on interviews with members of their own community. The successful pilot run of Fountain Voices at Hollywood High culminated in January, with a powerful presentation of work that explored homophobia, depression, and homelessness among teenagers. This month, Fountain Voices begins a partnership with Compton Unified School District, where we will serve over 100 students, longing to be seen and heard.

My time spent with these students reaffirmed what the last year taught me. And when my niece is ready to return to school and inevitably enjoys her first moment onstage, rather than prepare her for the darkness, I will encourage her to embrace all the light and love theatre shines on us.

France-Luce Benson (she/her), community engagement coordinator, Fountain Theatre

Human Healing

I began our time in quarantine in fear of what was to come during a prolonged and forced time with no real ending in sight. The feelings of sadness and uncertainty that washed over me were felt by so many, as we lost a sense of control over our lives. In my case, I had to face my home life head on and find a solution. The initial timeline of two weeks always felt made up and chaotic, because it was—because our country was reacting instead of responding. For me this began a very concentrated look at the ways we as humans have been reacting to our circumstances and merely surviving. The way that racism and anti-racism rose to a daily conversation at home and in the workplace was a result of lockdown.

Personally, I needed healing, and more than two weeks worth of it. I also needed to get out of my situation in order to heal from it. But what was that going to look like when people were losing jobs and opportunities were being canceled indefinitely? I had already been through so much and was looking for a break—a way to take a deep breath. In fact, well before lockdown began, I had requested the chance to work from home at least once a week, in order to be there for my daughter after her ballet class in Harlem.

What I did not imagine was the shift that would happen. While I have always known my strength, 2020 took me on a journey out of and into: out of a personal hell and into a period of transformation and true healing. I taught myself to livestream and produced, edited, and livestreamed a play over Mother’s Day weekend with the Parent Artist Advocacy League (PAAL) and eventually became their producing director, I worked on digital projects at the Public Theater and celebrated Harlem9’s 10th anniversary with a digital edition. I curated visual art several times and was mentioned in a press release from my own beloved Public Theater as we make our own cultural transformation. I am so proud of the outdoor installation #SayTheirNames and the soul work I put into that in the middle of my journey out of the toxicity of my home. It all happened at once in 2020. No ifs ands or buts: The rewards were high.

I pulled myself out through work in the hybrid theatre we were all creating. I leaned on and learned how many beautiful people in this industry had my back. I pulled myself out by making known the work I had been doing for years: the work of diversity before it was renamed “anti-racism.” Wherever the uplifting of Black stories is, I will be there. Wherever the creation of spaces for Black people across the diaspora to share their history is, I will be there.

Last year gave me a gift. It offered me a real chance to take back my voice, and 2021 welcomes me oh so much higher into my purpose, surrounded by lessons, loves and new and exciting professional and personal partnerships.

Garlia Cornelia Jones (she/her), producer, Harlem9

Me and My Friends

In March 2020, I was sent home from my first year of college in the School of Drama at UNC School of the Arts (UNCSA) on a spring break that was supposed to last only one week. Instead, I was torn away from my campus, faculty, and peers for nearly half of a year. Being isolated from a group of people I had so quickly fallen in love with over our short semester-and-a-half was really difficult. School had made me, for the first time in my life, an extrovert. I was constantly filled with love and adrenaline from my discovering of the individuals I was about to spend four years with.

Coming home was a complete system shock. Suddenly I had to learn how to be alone again. I had to navigate being a changed person in a place where nothing had changed. During those five months, I missed my people more than I’ve ever missed anyone before.

Finally, after months of counting down the days and doubtful speculation, we returned to campus in August. Somehow, even through masks and Zoom, we created a sense of normalcy. Things as simple as sharing a space with another masked person felt like an achievement. Acting with someone, even through plexiglass, felt incredibly precious. Sitting socially distanced outside, watching a devised production created by my peers through the windows of a historic inn, was unreal. I quickly realized how much I had taken for granted.

This school year, at least for me, has been about my friends and their work. I think we often get stuck in the notion that theatre has to “heal the world.” The world is, quite literally, too sick for theatre to heal it right now. Only a vaccine can do that. But I do think that we can use theatre to heal ourselves. My version of the trademarked “quarantine self-discoveries” found their way out of me through random 10-minute scenes. Though our audience was on Zoom, I got to direct a piece written by one of my best friends, a dream of mine since I first met her. I got to sit in an audience of six and watch the people most important to me perform a show they fought to have seen because it was important to them.

We did a lot of theatre that was for us. And as sappy as it sounds, these were the moments that kept me hopeful. These are the reasons I’m still here, getting a BFA in acting during a worldwide pandemic.

In May, I’ll be doing a show (with my friends) at a theatre company (started by my friend) in an outdoor amphitheatre with an actual audience (probably filled with my friends). In conclusion, I love my friends. They heal me. I cannot wait to watch them heal the world once this all ends.

Gianna Hoffman (she/her), a second year in the School of Drama, UNC School of the Arts

Essential Voices

As president of the Theatre Musicians Association and its Chicago area chapter, I spent my past year serving musicians who perform for live theatre amid the profoundly devastating impact of the pandemic. We (and I) have spent the last year:

- Assisting in organizing efforts, as Teatro Zinzanni musicians in Chicago won a groundbreaking card count and election certification with the NLRB for union representation amid the shutdown

- Keeping our community intact and informed via webinars about navigating the challenges of unemployment benefits, acquiring gear and expertise to perform at-home recordings, teaching over Zoom, coping with the stress on mental health of being locked out of the economy

- Passing progressive anti-discrimination, harassment, and bullying bylaw language in Chicago Local 10-208 to ensure musicians return to work with dignity in safe and respectful environments, and authoring return-to-work theatre protocols for musicians across the U.S. and Canada

- Joining our sister unions (IATSE, Equity, SAG-AFTRA) in lobbying elected officials for multi-employer pension relief and COBRA subsidies for musicians

- Hosting Zoom socials and video projects for our members to remain socially and musically connected while physically distant from one another

We have lost so much over the last year: Children who missed hearing an instrument live that could have awakened their artistic soul; music students and recent graduates who find their previously “uphill” struggle now a vertiginous cliff; gifted colleagues who are struggling, had to move, lost their homes, or “retired” against their volition. Every player and voice is as individual as a thumbprint, a unique frequency lost—the personification of “essential,” as art and artists are the very essence of our shared humanity.

The obstacles confronting our community are unprecedented and, as with any challenge, the only way out is through. My heart hopes for a “roaring ’20s” powered by the engine of arts and culture in our future. Large, seemingly insurmountable obstacles can bring out learned helplessness: “There’s nothing I can do,” “The problem is just too big,” “I don’t have enough time, resources, power to have any impact,” “I’m not enough,” “Someone else will take care of it.” But I think 2021 is going to be the year to normalize persistence and consistency—not busting through barriers, but standing united together to show that we did not go gentle into that good night. If you’re in the position to support the artistic community around you, please do so. Onward.

Heather Boehm, musician and music contractor

High and Low

This year has been a whirlwind of heartache and survival. My play 72 miles to go… closed a day after it opened Off-Broadway at Roundabout. Todd Haimes called to tell me the news while my husband and I were panic-shopping at Costco. I was seven months pregnant with our son, and gave birth in May at the height of the pandemic in New York. Our son was in the NICU for his first 10 days of life, but only one of us could visit at a time, so we weren’t together as a family until he came home. Two months into life with a newborn, our landlord kicked us out of our home and my father-in-law was diagnosed with Stage 3 cancer.

These past 12 months have been crisis after crisis, but through it all, I’ve still managed to write almost every day. I’ve been doing a lot of soul searching about the kind of work I want to make and who I want to make that work with and for. I’ve been thinking a lot about El Teatro Campesino and ways to make theatre accessible and equitable to everyone outside the wealthy subscriber model. And I’ve been thinking a lot about my own fear. Why have I spent a lifetime being afraid to write my most personal and vulnerable experiences? Maybe it’s time to do that.

Hilary Bettis (she/her), playwright

Grief and Choice

As a playwright, the best way I can describe what the last 12 months have been like for me are through the five stages of grief: the denial of what has been lost, the anger at our industry’s relentless attempts of finding a way forward without grieving what has been lost, bargaining as a coping mechanism for trying to control what was uncontrollable, a deep and massive depression unlike anything I’ve ever experienced before, and finally accepting that things might be different now and, perhaps, forever—and that is okay. I have lost theatre and found it again and lost it again and am finding it again. I have let it drift off to sleep and have raged at the earth to wake it from slumber. I still don’t know what I’m doing but I have learned that theatre is a choice. That we don’t have to endure toxic and abusive relationships if we do not want to—including with our art. We can walk away if we want to.

Isaac Gomez (he/him), playwright

Outward and Inward Change

True Colors celebrated closing night of School Girls; Or, the African Mean Girls Play on March 8, just a few days before everything came to a halt. At the closing toast, playwright Jocelyn Bioh remarked that prior to this staging, she had never had her work seen by an audience filled with the people she wrote for and the characters that populate her plays. Her words pushed us to consider what impact that feeling could have for more writers, so we started thinking about commissioning artists and inviting them into that experience from their first moments of creating a new work. As we commemorate the one-year anniversary of the closure of our stages, we are sharing the work of 10 new Black storytellers, and have developed and are developing new work that will appear on our digital and live stages in the next few months.

Our company has looked inward, too, as we seek to find ways to better serve ourselves as well as the community. The plagues of the last year remind us of the importance of time and space to process and heal. While we seek to advocate for and work alongside people demanding social action and accountability, we also believe in building a culture where we radically pursue joy and seek refuge from the pain of the process.

Personally, I’ve had the pleasure of spending more time in community, albeit virtual. Formal and informal collections of artists and administrators provide a respite from the frustrations of producing in an era of uncertainty. Weekly musings with artists on the True Colors Podcast reaffirms my desire to do the work. My daughter’s new “Zoom bombing” hobby has become a welcome distraction for any meeting.

As the pandemic lined up with plans, we had to undergo a strategic planning process. A push to expand our offerings and the staff to deliver, grasp a better understanding of the digital arena, and to establish ourselves as a leading regional theatre and a model for a contemporary Black theatre company has lead to a solid vision for the future. We thrive at the intersection of artistic excellence and civic engagement, and this last year has prepared us to be a better company, a better administrative and artistic home, and a better community resource when we re-emerge.

Jamil Jude (he/him), artistic director, Kenny Leon’s True Colors Theatre Company

Native Stories Rising

I hope that we will look back and say this was the moment that resources were finally equitably distributed to support BIPOC artists and the organizations that have fostered them. I’m hopeful that more Native stories will finally fill our stages, that people recognize the diversity of Native experiences, and that producing a Lakota playwright has nothing to do with whether you produce a Tlingit playwright or a Cherokee playwright or an Isleta Pueblo playwright—each and every Native story needs to be told. I’m looking forward to partnering with multiple organizations to produce the Native writers currently under commission with AlterTheater: Vickie Ramirez (Tuscarora), Blossom Johnson (Diné), Tara Moses (Seminole), Dillon Chitto. I also hope that theatres like New Native Theater, Spiderwoman, and so many who have been doing this work long before this moment in time are recognized by funders. I hope this is the moment we can point to when the economic disparity between Native theatres and PWIs ended. I also hope this marks a moment in time when storytelling sovereignty moves to Natives, and the process of non-Natives being the gatekeepers of what’s a “good” Native story ends.

As I look back over this past year, my heart still breaks that we haven’t been yet able to produce Vickie Ramirez’s Pure Native. And my heart breaks for all the BIPOC writers whose careers were finally starting to break open, including Diana Burbano, whose Rella Lossy award-winning commission, Ghosts of Bogotá, closed at AlterTheater just weeks before theatres shut down. I hope those careers continue to rise spectacularly.

We were able to pivot from the heartbreak of postponing Pure Native to the joy of hosting theatre workshops for Native youth, in which we fostered connections among working professional Native artists and Native youth. Those Zoom rooms—full of the kids’ wide-eyed wonder, heart-filled writing, and funny parodies—have been my favorite thing this year. I hope there’s more of that joy in the future.

I hope that the economic disparities get righted in time for these kids to truly build a career in the theatre. Each of these kids has such a voice! So many stories! It will be a tragedy if we don’t get to hear them all. A career for a Native artist would mean they have the freedom to tell their stories, the right to get paid a living wage, and the platform for their voices to be heard loudly. I hope the next time a study like “Reclaiming Native Truth” is done, invisibility is no longer the single biggest factor affecting Native outcomes. I hope that all Natives can see themselves represented in their full complexity in the stories we tell, and that I’m not a liar when I say to these kids, “Yes, you belong in the American theatre; this stage is your stage.” Because right now, today, I am still lying to these kids, and the American theatre is lying to BIPOC artists when it makes a similar vow.

I am working toward a theatre without lies. I hope we are capable of coming together to build it.

Jeanette Harrison (she/her), AlterTheater

Rejoin the Community

I believe the theatre industry will look back at 2020 as a moment when we finally engaged in creating social change across our sector. At Intiman, we spent the year gathering in virtual community with our audience, developing our board, and making partnerships for the future.

The pandemic hit as we launched a planned series of public conversations. These conversations were the centerpiece of our community-involved strategic planning process. Lockdown actually led to increased participation, resulting in deep, meaningful and sometimes tough conversations. Being in community, holding space for reflections on our past while dreaming for our future, was invaluable, and I’m beyond grateful to those 200-plus folks who chose to join us.

We also spent the full year investing time and intention into board growth, governance and development. As an arts leader, I can say unequivocally: It is much easier to do the work that live arts are uniquely qualified to do when your board has the literacy to move beyond 101 conversations on race and equity. It’s even more exhilarating when they are the ones challenging the group to learn together and consider new perspectives on these issues.

Finally, we heavily invested in the creation of an unprecedented partnership with Seattle Central College. This partnership includes the launch of a new Associate Arts degree in Technical Theatre for Social Justice and a new home as Intiman becomes the professional theatre-in-residence in the Erickson Off-Broadway and the Broadway Performance Hall. I fundamentally believe theatre is an art belonging to the people. It is our responsibility as custodians of these arts institutions to return it to them.

I am looking forward with joy to moving our operations, launching this new degree in the heart of Seattle’s gayborhood (also my home), welcoming people of all ages and backgrounds into this ancient experience of live storytelling, reimagined and (finally) inclusive.

Jennifer Zeyl, artistic director, Intiman Theatre

Organize and Push Back

Since the shutdowns in March of 2020, I’ve felt a multitude of emotions: loss, empowerment, resilience, disillusionment, rejuvenation, and more. It’s a layered state to be in while pinpointing why exactly I was drawn to theatre in the first place and how I’ve navigated within the theatre industrial complex since then.

In the last 12 months, I’ve focused on what my community is and how I can best serve it through my work in theatre. By creating spaces—even digitally—from affinity group meetings to events through my producing entity, the Sống Collective, I’ve found nourishment during a time of uncertainty and isolation. I’ve been awestruck by the amount of organizing, social justice work, and support pouring out of theatre professionals during this time. I’m inspired by the number of artists stepping into their power and finding strength in their voices to speak out for radical change.

We must push through the stagnation and complacency our industry has lived in for decades and move into a new era of American theatre that rectifies injustices and embraces equitable practices. Looking forward, I urge many of my colleagues who have finally acknowledged the realities within our industry to not fall back into upholding the oppressive practices our industry perpetuates and that they continue to investigate, push back, and reexamine their place within these systems as we move forward.

Jonathan Castanien, stage manager/producer

Thank God I Got Fired

I was in Atlanta teaching playwriting at the local university. I was just at the beginning of my teaching career: freshly pedigreed and widely produced with so much to offer my students.

Teaching was always my thing, and I feared that developing a career within the academy would squelch my passion for it. As the token Black man in the department, I ran into so many walls trying to navigate the court (a.k.a. the department). I was teaching under unnecessary supervision; having my lessons undermined in front of my students by said supervisor; being pressured into being a customer service rep for students who didn’t deserve the grades they wanted; and most importantly, I was seeking refuge from the institutional racism that all Black teachers face. I never wanted to leave a job so bad. The universe gave me what I wanted in the form of a global pandemic.

In March, I was let go from my job; my productions were cancelled; a theatre company in New York asked for their commission back; and to add the cherry on top, an ex-colleague asked me to vacate the room I was renting in their home. My anxiety went through the roof: Don’t these people know that life and death are right outside the door? Of course, they knew, but why would I expect them to care so deeply about my well being? One thing I learned from this pandemic: When it’s “every man for himself,” it really is every man for himself.

As a playwright, my job is to keep a finger on the pulse of society, to predict the future, and most importantly to mobilize my community around the fire. But the fire this time was actually burning the theatre down, fast, and it forced all of us inside to think. So I put on my thinking cap and downloaded every gem I could from my years as a student. My thinking cap finally combusted…

“I can teach online and develop my own practice!”

Now, plenty of playwrights have run their own workshops before, but not in these circumstances. With the World Wide Web in front of me, I cast my net as far and wide as I could and whaddayaknow—I filled my first class with 10 playwrights. Some were actors I had worked with, some were playwrights I didn’t know from a can of paint, some were colleagues I went to school with, some were professors at the own respective universities, some were still students who were still enrolled. This was really happening. I threw every dollar I could at Amazon, got all the tools I needed, packed up my car, and drove west to Los Angeles. I didn’t even think twice about it: Spirit told me to move. On April 20, I kicked off the inaugural group of the Playwrights Workshop with “My Favorite Things” by John Coltrane, turned on my camera, and never looked back.

But first things first: I couldn’t do this alone. After the first two classes, I called stage manager extraordinaire Olivia Plath and begged her to help run the room. Olivia and I met at Yale School of Drama right after Trump got elected. Our first play together was Wrong River at the Langston Hughes Festival of New Works. One thing I can say about stage managers: You’ll always remember how they made the room feel before and after you get to play. Never in my career has a stage manager made me feel so safe, respected, supported, and heard as Olivia did. Yale has a special way of putting life-long collaborators together. We later added Christina Fontana to the team, and with her we were able to expand the workshop and add on two more groups of playwrights.

By Jan. 31, over 65 playwrights and 100 actors came through to play at the Playwrights Workshop. By the end of this last group COVID-19 had claimed 400,000 lives. When we began last April, the count was only 40,000. But as the body count ticked higher and higher, my comrades and I dug in deeper. We challenged our playwrights to tell the story they’ve been dying to tell. We watched them beam with wonder as actors flooded our rooms and gifted some of our new writers the beauty of hearing their pages for the very first time. Everything I’ve experienced in the room pre-pandemic didn’t matter. I became the teacher I’ve always wanted to be. Thank God I got fired!

This pandemic brought in the most exciting year of my life. It truly is the best of times, and the worst of times. Without the Playwrights Workshop I wouldn’t have the nerve to say with my chest that I was a leader in the field, but dammit, I am a leader in this field. That’s what this pandemic is teaching me: to step up and take your place if you want one. Now, as I sit in my bunker, waiting for my turn to get vaccinated, all I can do is sit and hope that the sun is shining and the sky is blue wherever you are in the world. Next month this crazy idea that was birthed out of desperation is having its first birthday. Get ready for Year Two, Comrades! We got this. Onward and upward!

Josh Wilder (he/him), playwright

Grateful? Yes, Grateful

A most dubious anniversary, indeed! I don’t know if I want to celebrate this one each year. I had just opened my first play as incoming AD of Jackalope days before the shutdown. Then I spent much of that month in panic meetings at all hours cancelling first the opening weekend, then the entire run, then the next show in the season, then the entire next season we had planned. But hope was on its way in the form of a critical mass of BIPOC artists who have had enough and made every one of us finally not feel so alone in this industry. Which is a pretty cool feeling to have during isolation.

Even before the pandemic, 2020 felt like the “go time” switch got slammed on so hard the handle snapped off. I didn’t really breathe till New Year’s. Now that I have a bit of distance from it, I look back at the Beginning of the After Times with an enormous amount of pride. It feels so strange to say “pride” as I mostly look back and remember so much pain and mourning, but I’m proud we protected our people, I’m proud we were hiring artists, I’m proud we’ve been developing our digital branding. I’m most proud of the number of new plays we’ve aided in developing; I’m proud of the seeds we’ve planted for our future. I’m proud we stood on, and strengthened, our values of equity, decency, and representation.

We’ve been in the pandemic for so long now, it’s sometimes hard for me to remember just how much the industry was teetering and just how blindsided we were that this would be what tips us over. And it’s even stranger to say I’m grateful for this time. But I’m grateful. So many artists have relocated, taken new positions, left positions, exited the industry, and so many new artists are about to burst onto the scene. The landscape is shifting in a way I thought would take decades, and the potential that awaits is so very exciting for our future. We are simply not returning to the way things were. No longer. Never again.

This anniversary feels premature because the clock is still ticking. We’re not done yet. This pandemic will end sooner than we think, and then we’ll see if this gift of time yields real results. I hope so. I hope it all sticks and stays stuck as long as we can stick together. I volunteer as glue.

Kaiser Ahmed (he/him), artistic director of Jackalope Theatre Company

More Feeling to Do

Over the last year I repeatedly felt shut down, numbed out, and cracked open. I worked to align my values with my actions, leaning into the moments of peace, connection, joy, community, healing, and stability I found amid the chaos. Some of these moments included spending time with my mom and chosen family, moving in with my partner, production stage managing a socially distanced arts festival in the woods, co-cultivating and co-teaching a stage management for dance virtual intensive, and collaborating on the American Theatre digital issue in September which highlighted TGNC members of the theatre community.

That being said, between the pandemic, performing arts and live events shutting down, the racial uprisings, the election, and my personal life, I am still processing much of what happened over the last 12 months. I’m welcoming the space to continue to feel, grieve, and celebrate moments I did not have the capacity to fully experience during the height of the pandemic, and I am embracing the healing that processing these feelings will bring. I predict that I will revisit and feel through moments from this last year when returning to what used to be everyday activities: using public transportation or boarding a flight, running a rehearsal or calling a show, listening to a song that came out over the last year, finally getting to freely hug my friends and family, and thinking of lost loved ones.

My aunt Kathy was diagnosed with leukemia in April and died unexpectedly of complications in October, and I was across the country at the time. My mom called and let me say goodbye to her over the phone, and I then immediately booked a plane ticket. After properly quarantining and testing, I spent the next four months with my mom. Though the loss of my aunt without a real goodbye has been painful, the time spent with my mom was an unexpected gift I will always cherish, and likely would not have happened had everything been “business as usual.”

The last 12 months have demanded that I reexamine, reshape, and reaffirm ideas I have long held about myself, my work, my priorities, and the world. This process has led me to stand up for my values, take care of myself, and prioritize my needs and the needs of my loved ones in ways I never had before. I fully intend on incorporating those lessons into my work. I will proudly remember how so many in the theatre industry rallied to help check in and take care of one another despite the immeasurable change and loss brought on by COVID-19.

I hope to also remember this as the year of reimagining, in which anti-racist, inclusive, and holistic practices become the standard moving forward in the theatre industry. Only time will tell. I have no interest in going “back to normal.” Thankfully, we can only move forward from here.

Kasson Marroquin (he/they), stage manager

The Task and Technology of Theatre

Because I teach at a university, these past months of my life have been defined by Zoom. I teach classes, conduct rehearsals, attend readings, and develop new projects all online. I know how lucky I am to have a full-time teaching job right now. My paychecks haven’t stopped. But as the rest of the universe ground to a stop, my world sped up.

A few years ago my partner went through breast cancer treatment. I actually look back on that as a really good year. We were in it together. What mattered was clear. Our values were un-confused. We needed each other and appreciated each other and so our relationship got stronger. I feel similarly about this pandemic year. Some things that are essential to theatre, the reasons why we make theatre, and what we get out of theatre have become much more clear to me.

Like others, I was in the middle of rehearsing a show when the world shut down: The Method Gun by the Rude Mechs of Austin, re-devised by me with my Wesleyan University student ensemble. We, like others, pivoted to Zoom. My biggest recollection of early lockdown is the feeling of being on a life raft with my students. We needed each other. Making performance has always required us to be together, but with the world now metaphorically broken apart, gathering together became the most important aspect of our process. Theatre made it possible—was actually the only means we had—to be in community with others. In the time of COVID, the task and technology of theatre began to ring clear.

One of my favorite moments of the process was when I was working with an actor who was Zooming from her childhood bedroom. She asked me if I still wanted her to light a piece of a paper on fire, as we’d planned for the live version. “How do you think your parents would feel about that?” I had to ask. As it turns out, they were fine with it—but then the production team got involved. They were like: “Okay, so you are having fire. Where is the closest fire extinguisher? What about the smoke alarm in the hall? You better unplug the smoke alarm.” They tried to do their normal job inside her house: “Where is the bucket of water? Can you show us the bucket of water?”

But nothing is normal anymore—and that is a very good thing.

This question, “Is it theatre?” has been bandied about a lot. I don’t find it a useful question. Sure, we can call it theatre. I like thinking of theatre as an exchange between a performer and an audience person, so in that sense, yeah, it’s theatre. Otherwise, no; it is its own thing. It’s definitely not film. It’s definitely not TV. And it’s definitely not live theatre. It’s Zoom performance. And we can feel things from it; we can feel connection. We can share a performance with someone halfway around the globe! Isn’t it amazing, how close we now come to each other? How we offer tacit invitations to come inside our homes, just by clicking on our videos? I love it. I love that the aesthetic can be high on humanity and low on technology, that by leaning into the site of Zoom my theatre can become more human, more intimate.

The pandemic has taught me some big lessons about the importance of keeping care and relationships at the top of my priority hierarchy, both in life and in theatre. That personal lesson of mine is being played out in our industry as a whole. In the future, I hope this whole year is seen as a necessary pivot point for theatre. There has been unasked-for disruption to our field due to COVID, and asked-for disruption thanks to Black Lives Matter and the We See You White American Theater movement. An accessibility conversation has jumped to the forefront of everyone’s attention. Thank God theatre is there to give us a shot of (and at!) togetherness—now we just have to get better at the “together” part of it.

I am expecting, hoping, and counting on these conversations to shape our field long after we’ve all been vaccinated. Whether on my university campus or with my PearlDamour collaborators in rehearsal rooms, I will do my part to keep them alive.

Katie Pearl (she/her), theatremaker

Essentially Inessential

Eight months before the COVID shutdown hit, I’d started a new job at the Chicago Reader. The week before the shutdown, I was getting ready to edit our spring theatre and dance preview issue—one of the biggest of the year—and looking forward to moderating a panel for the paper at Steppenwolf about emerging BIPOC leaders in Chicago theatre.

Well. As the old saying goes, if you want to make God laugh, make plans. (Apparently this applies even to agnostics like me.)

I still have the job, which is a miracle and a blessing (even for an agnostic like me). But now we’re all working from home for the foreseeable future. Goodbye, in-person office camaraderie. As someone who had spent over 10 years as a freelancer before taking the job, I was starting to relish the daily company of colleagues again. Ah, well. Zoom happy hours can be fun, right?

Prior to the shutdown, I was at the theatre three to four nights a week (less than many of my peers). I assigned and edited reviews and features on performance from up to a dozen writers every week. The Reader, like every other media outlet, took big hits in advertising revenue. Fortunately, we were already on the path to becoming a nonprofit before the pandemic. We went through some months of furloughs and pay cuts, but—thanks to PPP money and lots of donations from people who’ve come to rely on us over our 50-year history—my dears, we’re still here.

I mostly don’t think I can begin to predict what this year will mean for theatre going forward. I’m far enough removed from covering Broadway and commercial theatre in general that, while there have been commercial casualties in Chicago (the Mercury Theater and improv/sketch powerhouse iO come immediately to mind), my ongoing concern has been with the midsize nonprofit houses—those that have fixed costs, including real estate, but few ways of creating revenue without live productions. So far most of them seem to be holding steady, for which I am grateful.

What have I been doing with myself? First of all, I’ve been wearing out all the synonyms for “virtual” and “online” in writing about the shift to performance onscreen rather than onstage. I’ve been admiring how quickly so many companies ramped up their digital components, including online classes, public podcast series, and more. I’ve been writing and editing more features about the offstage news that rocked Chicago at least, from the departure of Andrew Alexander (the co-owner and CEO of Second City, who stepped down last June in the midst of heightened attention to institutional racism at the comedy behemoth), to news of shifts in leadership at theatres big and small in town. Many of the new artistic directors are Black: Jon Carr at Second City, Regina Victor at Sideshow Theatre, and Lanise Antoine Shelley, just named artistic director for the 20-year-old House Theatre of Chicago.

It’s impossible for me to think about the year just past without thinking about the summer of protests and the anxiety about the election (and subsequent deadly insurrection). The publication of the BIPOC Demands for White American Theatre opened windows on a lot of stale air and toxic bromides about equity, diversity, and inclusion, onstage and behind the scenes. (And of course, among those of us who review and report on the lively arts as well.)

The biggest takeaway I have from this year, honestly, is that I am the least essential of workers in the theatre realm. I’m not sure I’m supposed to say that out loud, but it feels pretty on the nose. Of course, it was always true that theatre exists, whether we write about it or not, whether we review it or not, whether we praise it or not. But in a year when theatre artists really had to reimagine what their world looked like, what theatre means when there’s not a live audience, and what storytelling means when it’s painfully clear that we’ve done a bad job overall of centering stories that tell the whole truth about who we are as Americans—what do I have to offer?

I feel less and less like a critic and more like someone whose job is to listen, describe, and try to provide some small measure of helpful context, given the personal limitations of my privileged POV as a middle-aged white woman in America, and the fact that I’m reeling like everyone else from All the Things that made up 2020.

So maybe what a year with a different kind of theatre has taught me is how to let go of my own precious sense of self-importance and surrender to loss and change. Because those are the only things of which we can be certain.

Kerry Reid (she/her), critic and journalist

Will We See the Same Again?