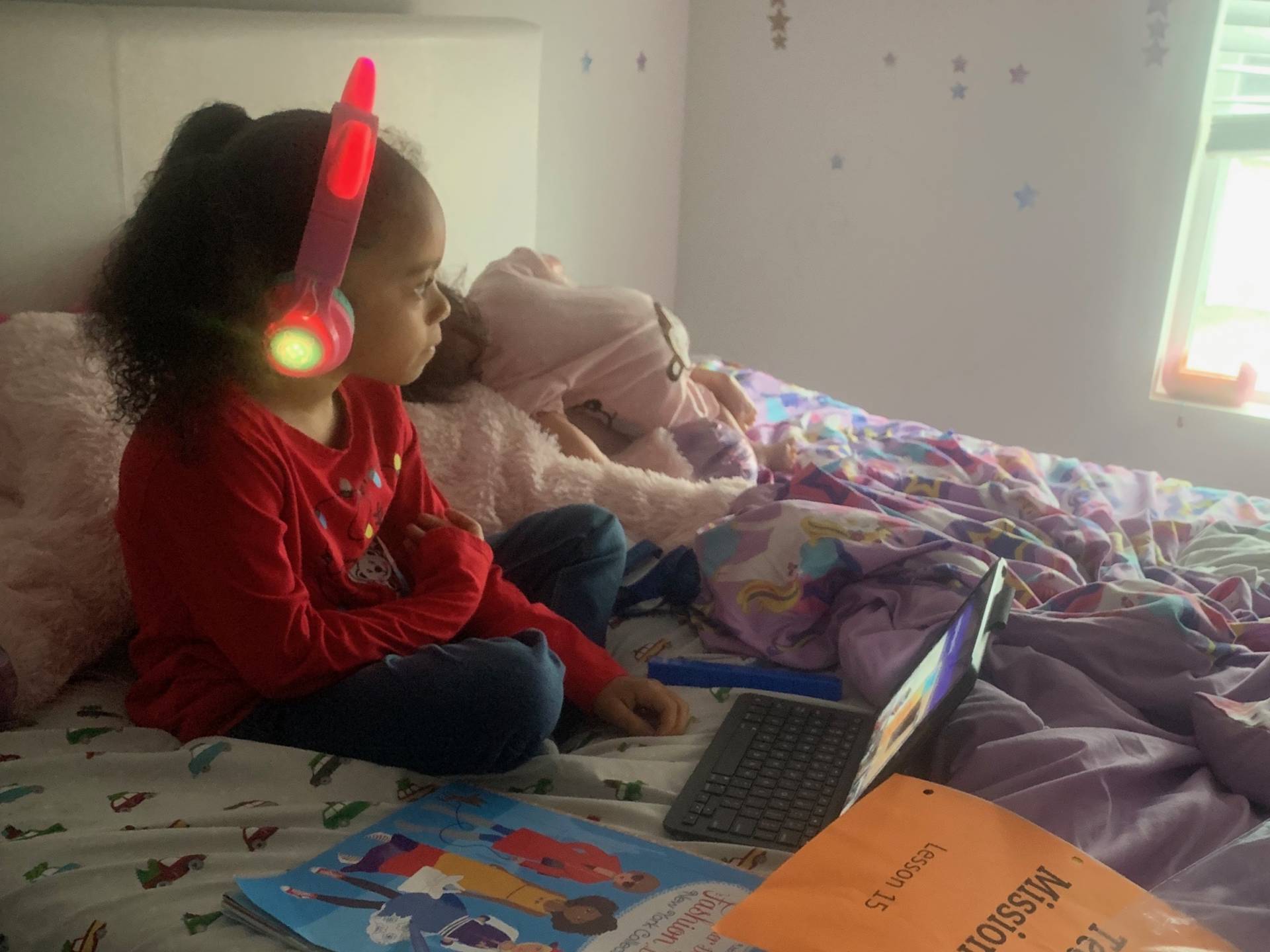

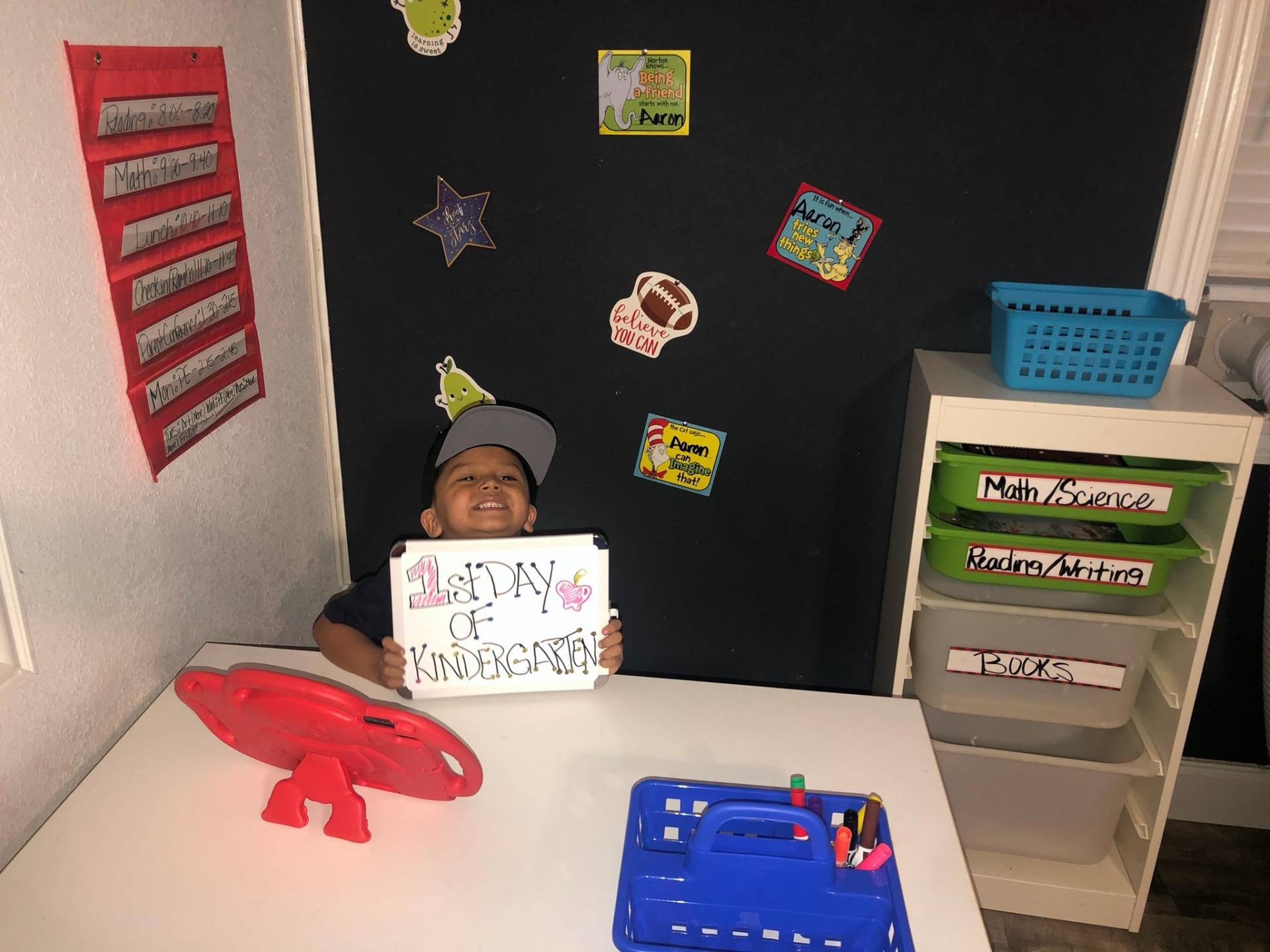

Parker, who is a pastor and children’s advocate in Raleigh, North Carolina, said her family was straining under the intensity of what she had looked forward to as a seminal year in her child’s life.

“I find the grief about the lost semester of school to virtual learning (the social interactions and experiences I can't replicate at home) comes in waves and at unexpected times,” Parker said in her email.

Kindergarten is designed for young children, who learn best by doing. And while pre-literacy and math skills are covered, building block towers, playing make-believe and mastering the playground equipment are also key elements of this critical grade.

“I don’t want to pit one grade against another,” said Laura Bornfreund, the director of early and elementary education policy at New America, a progressive think tank. “But the foundational knowledge, the skills to be able to learn and do well in school later are so important. Kindergarten matters a lot.”

Approximately 3.7 million 5-year-olds were expected to enroll in kindergarten this fall. In pandemic times, most of them — 62 percent by one estimate — were slated to start the school year sitting at home in front of a computer.

Asked what 5-year-olds stand to lose if their entire kindergarten experience is moved online, Bornfreund was concise: “All of it.”

And children who already have the least stand to lose the most. Research has shown that high-quality early education benefits children, especially children from low-income families, through to their adulthood. A strong start can improve academic achievement, financial independence, even heart health. For the most vulnerable students, missing kindergarten could become a permanent handicap.

As consensus grows that schools are not the superspreaders of the virus they were initially feared to be, many districts are working to bring their youngest students back to school. However, students of color were the least likely to return to school in person this fall. A September survey of 677 school districts found that 79 percent of Hispanic students, 75 percent of Black students and 51 percent of white students wouldn’t have the option of in-person learning in September, according the survey by the news service AP and Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news organization focused on education.

(Schools district plans are changing so rapidly that it is impossible to pin down concrete numbers that can be counted on for the whole year, so snapshots like those provided by surveys offer the best information we have at the moment.)

If missing kindergarten “could happen equitably it doesn’t seem like a tragedy to me, but the fact is that kids’ experiences are just going to be incredibly unequal,” said Mimi Engel, an associate professor of education at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who studies how children learn in kindergarten.

Nobody is prepared for this, Engel said, including teachers.

“We already have something that’s ‘good online kindergarten’ called Sesame Street,” said Engel. “That’s quality programming originally targeted to low-income kids. You’d want something as engaging as that. And to expect a teacher to create that is unreasonable.”

What life looks like for 5-year-olds this year will vary immensely depending on where they live, who they live with and whether their schools are offering instruction online or in person. What is certain is that many, if not most, of this year’s kindergartners will enter first grade knowing less than they would have learned in a typical year. And the variation between what different kids know will have grown.

“We can’t just ignore going into first grade that kids didn’t have kindergarten,” said Bornfreund. “Without the recognition that this year was just a loss, that’s going to be to the detriment of kids.”

In West Virginia, kindergarten teacher Holley said she feels better about the experience of her in-person students. By early October, two of her online kindergarten students were attending in person and she expected more to follow. Nationally, more than a third of children (about 38 percent) were attending school in person either a few days a week or every day at the start of the school year. Anecdotally, it’s going better than expected.

“The kids are handling it remarkably well,” Holley said of her students, two thirds of whom come from families living in poverty. “I think a lot of us thought, ‘Oh the kids will never wear masks.’ They are doing just fine.”

Holley said the staff at Rupert Elementary School in Crawley, West Virginia, where she teaches, has pulled together and she’s never felt more supported. She thinks they are doing everything they can to keep in-person learning safe. That doesn’t mean she isn’t terrified sometimes.

“My biggest fear is that a child will get the virus, transmit it to their caregiver and then the caregiver will die and the child will have no one,” she said. “Children need to be in school; it’s the most important thing. And it’s a pandemic. This is not going to be a normal year.”

Safety concerns plague parents too. And yet, of the many families interviewed for this story, those with kids in school were the happiest.

Vivian Olsen, 5, goes to school four days a week in Eagle, Colorado. She thinks of her masks “like an accessory,” said her mom, Robin Olsen, 47, who works remotely for a Dallas-based investment firm. More importantly to Olsen, Vivian comes home each day proclaiming it to have been “the best day of my life.”

“We are so grateful for our teachers and educators for showing up EVERY day for our children,” said Olsen by email. “Most of them are parents too — it must be a lot to juggle and I am humbled by their courage.”

Adding to the juggling act, some districts are frequently switching schedules. In State College, Pennsylvania, parents are getting a notice each Friday about whether they will have in-person school or virtual school.

“It was the first time in almost six months I received a solid block of time to work that was quiet and without interruptions or distractions,” said Tiffany Mathews, 44, of her twins’ first week of kindergarten in State College. Then the Covid-19 infection rate in the area jumped and school moved online.

“Their teacher is great and very helpful,” said Mathews, who works as a program coordinator for science education outreach at Penn State. “However, trying to work with kindergarteners going to school at home is chaotic and productivity for my work has hit a wall (again). Not sure how this is going to be sustainable for nine months.”

For many teachers and parents, however, the risks of in-person school simply feel too high.

Jennifer Callahan of Redmond, Oregon has taught kindergarten for 25 years. Her husband’s fragile health made her think she might have to quit her job this fall if teaching in person was her only option. He’s had two recent surgeries and she didn’t feel safe going into a classroom every day and then possibly bringing the virus home.

Instead, she volunteered to be her district’s kindergarten teacher for the students who opted to go online all year. Her 42 students come from all eight district elementary schools, she said, representing both the high- and low-income areas of her small city in central Oregon. Their families have chosen the online option, often because of health conditions in their own homes, and signed a contract designating an adult who will supervise learning at home.

She said it’s a relief to feel that none of the adults involved expect perfection from each other. “They have asked for grace as well as said they would provide grace on my part,” she said of the parents, grandparents, older siblings and babysitters she’ll be working with all year long. “It was comforting to find out that they wanted that flexibility as well as being willing to provide it.”

Callahan has come up with dozens of ways to make online kindergarten work. Kids show they can identify letters by finding them on the keyboard and typing them into the chat box. Callahan leads “brain breaks” mid-lesson so kids stand up and move for a minute. To get to know their classmates, she has kids run to find certain items in their house and then hold them up in front of the camera. There’s crazy hat day, guest speaker day, pet show-and-tell day. She’s hooked her document camera up to her video feed so that kids can see her writing, and a colleague created digital versions of their social-emotional teaching materials. She introduced estimation by explaining to kids that she now keeps chickens — a pandemic hobby — and asks them to estimate the number of eggs in a basket she holds up for them. She hopes to take any student who wants to come on a socially-distanced snowshoe adventure this winter.

Callahan said that to preserve her optimism she had to stop paying attention to negative comments about online kindergarten, which can seem ubiquitous on her social media. “We didn’t choose this,” she said. “And we have to find a way to make it work.”

Many public school families have already given up trying to make it work and are simply opting out. Firm national figures are not yet available, but a research team based at the University of Oregon estimates that as many as 600,000 fewer children than expected have enrolled in public kindergarten this fall. If that’s accurate, it would be about a 17 percent decline in kindergarten enrollment. According to the surveys the team conducted, nearly half (47 percent) of parents reported that they could not manage having their child in kindergarten along with their other responsibilities.

The trend is widespread. In Los Angeles, 6,000 fewer kindergarteners showed up for school this fall, a 14 percent drop from fall 2019. Washington state saw a 14 percent drop in kindergarten enrollment as well. In Philadelphia, kindergarten enrollment was down 25 percent.

Michelle Blanchet, 35, a teacher training consultant and mom to a kindergartner and a first grader, has decided to homeschool her kids, at least until the family moves to Switzerland in February. Though they currently live in Leesburg, Virginia, Blanchet’s husband and children are Swiss. The Blanchets had already planned to move, but “the political climate and mismanagement of the pandemic have definitely created more of a sense of urgency,” Blanchet said.

In the meantime, Blanchet said she picks a theme each week and makes the lessons age-appropriate so that both of her children are learning at their current levels.

“Honestly, I think it takes me a fraction of the time it would to sit with my children and do distance learning (and I think hands on learning is much higher quality),” Blanchet said in an email.

Some parents who would have used the public schools have enrolled their children in private schools or decided to pay special child care centers to supervise their kids using online public school programs.

Teddy Brown, 5, lives a five-minute walk from his local elementary school in Columbia, South Carolina. His parents bought the house precisely because of that short walk, said his mom, Jessica Brown. And yet, this year Teddy started kindergarten at his Catholic parish’s private school. Brown, an economics professor at the University of South Carolina, knows her family is lucky to be able to afford this option. She also thinks it didn’t have to be this way.

“I feel a bit abandoned and betrayed by the public schools,” Brown said in an email. “If it’s safe for daycares to be open and caring for 4- and 5-year-olds, then I think they could have at least tried to open kindergarten. Instead, they’re treating it like an all or nothing decision. Either the entire school system is open or it’s closed. We need to do better for our youngest kids.”

It remains to be seen whether families like the Browns will return to public schools when they reopen, whenever that may be.

And when schools do reopen, this missed year will have to be accounted for, said kindergarten expert Bornfreund. Indeed, first grade teachers should be prepared to start their 2021 school year in more of a kindergarten mindset, she said. She wants to see districts bring kids to school next summer, if it’s safe, to stem learning loss. And she hopes educators use the moment to step back and think deeply about what makes kindergarten so important and then focus on that.

In the meantime, she said, offering social-emotional support to young children and their families is going to be paramount for the 2020-21 school year.

“Understanding where they are will help the academic learning,” Bornfreund said. “This is just an especially challenging time.”

Despite it all, there are some moments worth savoring, said Esther Berg, 46, whose youngest is enrolled in online kindergarten in Springfield, Virginia. Sometimes, during class, her son will reach over and grab her hand.

“Being able to stay with him and see him throughout the day has been bittersweet for me,” said Berg, who works in communications. “I’m thrilled to be there when he laughs and enjoys different parts of his day, but feel like I’m intruding on a part of his life that should be exclusively his. It’s hard.”

It can also get weird. In Boise, Idaho, Elizabeth Lion, 5, opened her phys ed class link recently only to find a YouTube video of someone twerking, a booty-shaking dance move, instead of playing soccer. “My younger boys do the PE classes with my kindergartner and they were confused about why they had to ‘do stuff with their butt,’” said Elizabeth’s mom, Kate Lion, 37.

The link, posted by accident, was deleted by school staff as soon as Lion, a stay-at-home parent, alerted them to the error. Overall, she said that to the extent she could drop the idea of Elizabeth getting a “normal” kindergarten year, online school was going pretty well.

“I had to realize that my expectations are not hers,” Lion said. “She doesn't know what she is missing so she doesn't miss it.

"later" - Google News

October 27, 2020 at 02:41PM

https://ift.tt/31MZTyJ

What Kindergarten Struggles Could Mean for a Child's Later Years - MindShift - KQED

"later" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KR2wq4

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "What Kindergarten Struggles Could Mean for a Child's Later Years - MindShift - KQED"

Post a Comment